Four months back, convinced that I could repair a broken Omega Speedmaster for less than the cost of a new one, I took a flyer on a collection of parts that were being offered on eBay. The pieces, when assembled, would compile about ninety percent of the watch in question- a 1967 Omega Speedmaster Professional (model no. 145.012-67). Still to be acquired would be the dial, bezel, caseback, crown, pushers, and three missing hands.

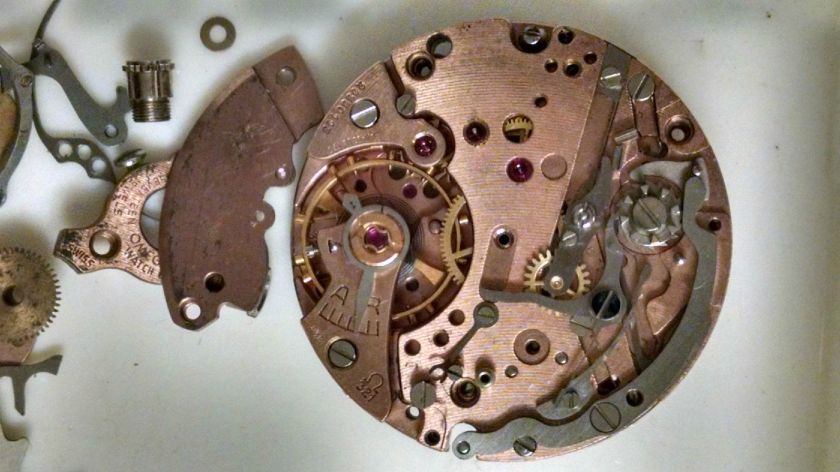

Before placing my bid I carefully examined the images provided by the seller to ensure some of the more difficult to find bits were included with the lot. Of particular interest to me were the pallet fork, balance, hairspring, and the chronograph levers and springs. A little bit of research confirmed that replacing pieces of the movement could prove difficult and be exceptionally expensive.

I was fortunate enough to meet the seller in person following the auction and I asked him why he had decided to part out such an iconic timepiece. He replied that the watch had never functioned properly and he had attempted to service it but was quickly in over his head. With the watch in pieces he visited an Omega boutique but was advised the minimum cost for reassembly would be in excess of six hundred dollars and this assumed the watch operated properly to begin with. At that point he decided to part it out. Unfortunately for me, the original dial, bezel, and caseback had already sold.

I thanked and paid the gentlemen and accepted my prize- a semi assembled Speedmaster in an Altoids tin. Now it is important to note that as of this date I had absolutely no experience repairing watches whatsoever and I had just accepted as my first project one of the most iconic timepieces of the 20th century. This was the Moonwatch. A timepiece that can sell for several thousand dollars. A timepiece with a movement that has not been in production for over forty years- with limited parts availability, and a chronograph to boot. Heading back home I wondered if I may have made a very costly mistake; my wife in the passenger seat held the Altoids tin gingerly as if it contained nitroglycerin.

I immediately began researching watchmaking and purchased the tools necessary for a rudimentary repair job. My wife surprised me with a small watchmaker’s desk on my birthday and I invested in a set of Bergeon screwdrivers, Dumont tweezers, and a dissecting microscope. I set about reassembling the movement to determine which parts were missing.

I discovered in watchmaking the learning curve can be a little rough. The first thing you realize as an amateur is that every part is so much smaller than you expected it to be. Next you find that coordination with tweezers is an acquired skill and watch parts have a tendency to rocket from the tips of the tweezers at great speed. You also discover that you do not know intrinsicly which screw goes into which hole!

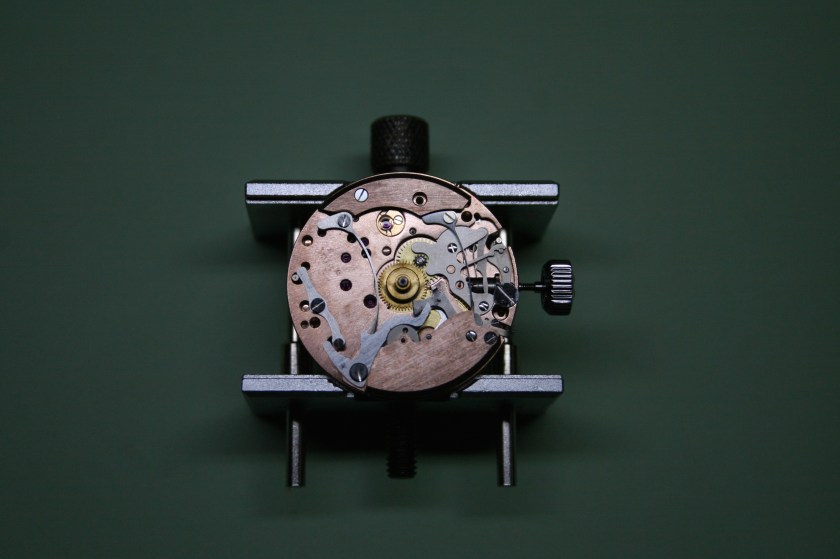

Once I reassembled the majority of the movement, I could see that the hour recording wheel, minute recording wheel, minute recording pawl, and pawl bridge were missing along with many screws.

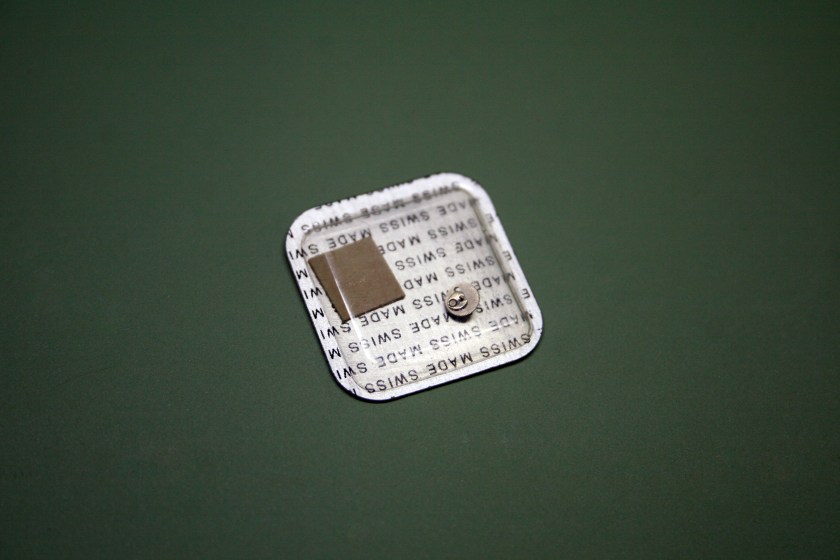

A query on the NAWCC forum led me to a watchmaker who had the missing parts for a fair price. I placed an order and proceeded to break down the movement.

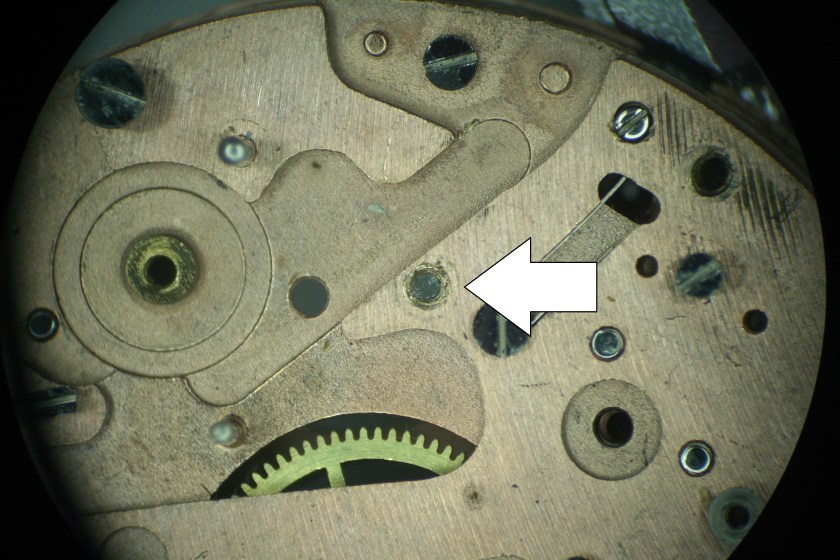

It was at this point that the first problem became apparent. The chronograph blocking lever screw had been broken off in the the plate! A thread or two of the screw still held and the seller had clandestinely screwed what remained back into the plate. Sneaky yes, but I had expected there to be issues so this wasn’t too much of a bother.

The solution for removing broken screws is to soak the plate in a mixture of alum and warm water. The alum oxidizes the carbon steel screw without damaging the brass plate, however in this instance there were a few steel posts in the plate for the chronograph levers as well as some steel eccentrics. I didn’t want to drive these out the plate but if I didn’t then how would I protect them from the alum bath?

The answer came again from the NAWCC where a helpful forum member suggested coating the eccentrics and posts in wax before placing the plate in the alum bath. I elected instead to use a bit of silicone caulk which worked like a champ; the caulk came away easily following the bath with a bit of pegwood and elbow grease.

Following a soak in the ultrasonic cleaner, the movement was ready for reassembly. I started by installing a new mainspring in the barrel and here the next problem became apparent. The gear teeth on the mainspring barrel were damaged. Since there was no way to repair this, a new barrel needed to be ordered.

Once the new barrel arrived I was ready to assemble the gear train and test the movement.

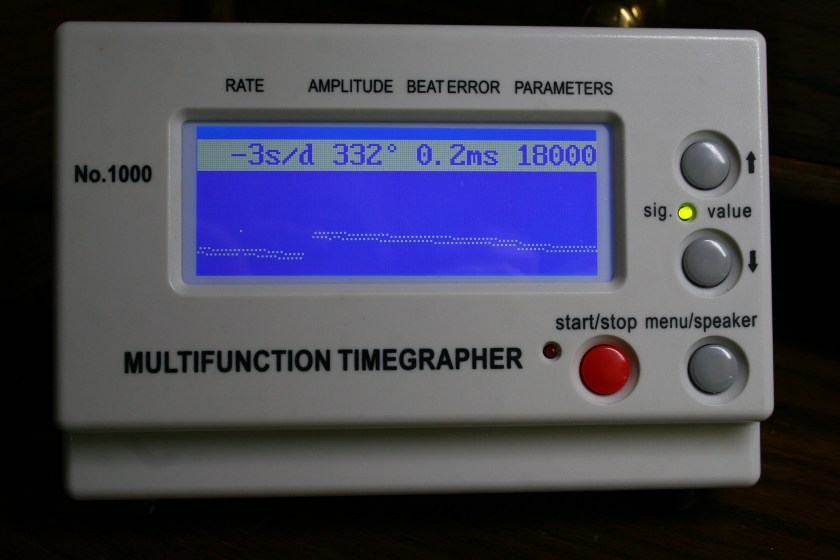

I had expected any real problems would become apparent once the balance was installed and braced for the inevitable but instead I was pleasantly surprised. The watch kept perfect time.

With the base movement ticking away properly, I could begin work on the chronograph layer. This would have been a major challenge had I not already discovered two wonderful resources in the form of WatchGuy’s website and a complete collection of the Esembl-O-Graf. WatchGuy is an exceptional watchmaker based in the UK. He has serviced many Omega watches and posts detailed analysis of each service along with high quality images. Esembl-O-Graf is a twenty-eight volume set of repair guides specific to chronographs manufactured in the 1940’s and earlier. The movement in the Omega Speedmaster is based on the Lemania CH27 movement which is covered in volume 14 of the Esembl-O-Graf set.

I worked my way, step by step, through the Esembl-O-Graf and the chronograph began to take shape.

Once the chronograph was together adjustments were made under the microscope to ensure the proper depth of the gear teeth and confirm elapsed minutes and hours were being registered. With everything operating properly it was time for a quick pat on the back before installing the dial and hands.

I had procured a replacement dial, set of hands, tachymetre bezel, and crown from a supplier in San Francisco. These were original Omega parts so the watch would look as good as new when complete.

I searched for a replacement caseback but found them to be rarer than hens teeth. A new one can be had from Omega but it would have the wrong reference number stamped on the caseback (145.0012 as opposed to 145.012-67) and as crazy as it sounds this would severely impact the resale value of the watch down the road. A complete case with caseback was purchased from a seller in Portugal. It was expensive but came with the crystal and both pushers already installed so I parted with the my original case to offset the cost.

One of the pusher stems was bent but this turned out to be a simple repair; the crystal polished up nicely with a bit of PolyWatch. I replaced the pusher gaskets and caseback gasket with new ones before re-casing the movement.

And there you go; one complete Omega Speedmaster Professional 321 calibre Moonwatch! The experience of restoring this iconic timepiece is one that I shall not soon forget. I had to replace two missing wheels, the two missing pusher extensions, the damaged mainspring barrel, crown, dust cover, dial, bezel, case, hands, and quite a few screws but when it’s all said and done there is no doubt in my mind that it was worth it.

I still need a bracelet or strap though. I have a feeling I’ll go for one of these reproduction NASA Nato straps that can be had from the UK- much more economical than the Omega bracelet and I think better looking too.

Dude!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful!

LikeLike