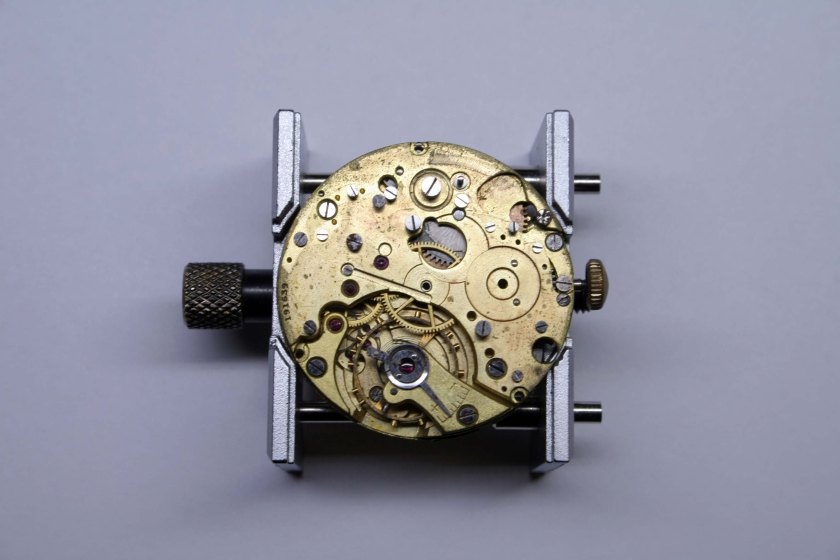

Here is what I consider to be a very special piece even though it’s missing some of its most important bits. This is a Universal Genève Uni-Compax chronograph from around 1942. The movement was most probably fitted in a solid gold case which at some point went to the smelter and may not be replaceable. Regardless, I was excited to get my hands on the piece because it’s a chronograph movement I’ve not worked on before.

In their time, Universal was a prolific producer of exceptional chronographs. Up to the 1960’s, before they were acquired by Zenith, Martel served as the sole supplier of chronograph movements to Universal. Their movements powered the Uni-Compax (“Compax” being short for “Complication”), Tri-Compax, and Aero-Compax among other models. Although I consider the Tri-Compax to be the Holy Grail of watches, I’m content to tinker with the more humble Uni-Compax here.

In their time, Universal was a prolific producer of exceptional chronographs. Up to the 1960’s, before they were acquired by Zenith, Martel served as the sole supplier of chronograph movements to Universal. Their movements powered the Uni-Compax (“Compax” being short for “Complication”), Tri-Compax, and Aero-Compax among other models. Although I consider the Tri-Compax to be the Holy Grail of watches, I’m content to tinker with the more humble Uni-Compax here.

This movement came from an overseas seller in a ziplock bag with many other chronographs, all in varying states of despair. I purchased the collection at a time when my confidence was running high and a dozen broken chronographs was not the definition of hubris. Slowly I’ve been working my way through the bag uncovering a few gems here and there, but also many gremlins along the way.

My initial assessment of the movement was positive; everything that should be attached seemed to be although the Escape Wheel sat at a odd angle suggesting a broken pivot. The movement emitted a strong odor of denatured oil.

The Balance Wheel moved freely confirming the pivots were still intact which was hardly expected as this movement lacks shock protection. Ominously though, the regulator was pushed far to the left- this could be an indication of a Balance Wheel or Hairspring which had issues. The chronograph levers and springs were speckled with rust.

Under the dial things looked a bit tidier although there was the expected rust in the keyless works.

At this point you’ll be forgiven if you think to yourself, “Well this chronograph looks just like the rest of them”, which is… true, but still it is special in some subtle ways.

This particular chronograph movement, the Universal 285, is a Column Wheel chronograph much like the Lemania, Venus, and Valjoux movements I worked on earlier. In these chronographs, a wheel with vertical columns is used to control the on/off switching of the chronograph (time recording) mechanism. Pushing the start/stop button results in the rotation of the wheel which in turn activates various levers to engage or disengage the wheels of the chronograph. These Column Wheel chronographs fell out of favor in the late sixties as they were more expensive to manufacture then the Cam Operated chronographs (although they’ve since seen something of a renaissance).

Another special feature of this movement is the Breguet, or Overcoil Hairspring on the balance. The overcoil is named after Abraham-Louis Breguet who developed it to improve isochronism. Although watches fitted with overcoil hairsprings were common in the early 20th century, the development of new tooling and materials for the production of watch balances have made overcoil hairsprings more of a luxury feature today.

A proper service involves removing the Balance from the Balance Cock for cleaning. On watches without shock protection, this step is also required to gain access to the retaining screws for the upper balance Cap Jewel. To free the balance from the cock I needed to carefully rotate the Regulator Boot and lift the edge of the hairspring from between the Regulator Pins. It was a bit fiddly (most movements with overcoil hairsprings simply do away with the boot) and had to be performed with bated breath lest I impale the hairspring with my oiler and relegate this watch to the scrap heap.

Having removed the chronograph levers, springs, and balance cock, I was getting close to the biggest challenge thus identified- the damaged escapement. Until the Escape Wheel was removed it was unclear exactly where the failure lay.

Removal of cock confirmed the escape wheel was intact but that the pivot jewel was damaged. This wasn’t terribly unfortunate as the jewel is cheaper than a replacement wheel.

Shortly thereafter, removal of the top plate revealed a broken Click Spring. This was terribly unfortunate as replacements are very difficult to come by and can be pricy.

With this setback I continued breaking down the movement for cleaning knowing full well that I wouldn’t be able to complete the job for a while.

I finished disassembling the movement and ran it through the cleaner then packed it away until a replacement jewel could be had for the escape wheel.

Funding for the jewel came through swiftly and set to work pressing in the replacement. I must be getting better at this watch repair stuff because I successfully ordered the correct jewel this time (something I still struggle with when measurements can come down to the correct rounding of a hundredth of a millimeter).

Some time later a replacement click spring was supplied by Scotch Watch and I was back in business.

Martel was absorbed by Zenith in the late 1960’s. Formerly they had supplied movements to both Universal and Zenith (although for a time Zenith also used movements from Excelsior Park). Once married to Zenith, Martel ceased supplying movements to Universal who instead turned to Valjoux for their chronographs. The craftsmen for Martel would go on to produce Zenith’s automatic El Primero chronograph movement which is considered the finest chronograph movement even today. Of course, what this meant for me is that any further replacement parts would be difficult to come by. Thus I proceeded to reassemble the movement with extreme caution.

Now, previous experience has taught me that a watch movement will only function properly if you put everything you’ve got into the service. Extreme cleanliness is a must. Each jewel hole must be carefully cleaned by hand before the movement is run through the cleaner. Each hole must be checked and cleaned again after coming out of the cleaner. Each pivot must be checked to ensure it’s properly burnished. Oil must be carefully measured and applied- too much or too little will hinder timekeeping. The wrong viscosity will hinder timekeeping or worse yet, escape the jewel. All steel parts must be demagnetized. The list really does go on and on, and every day I learn something new that results in further refinement of my technique.

Sometimes you’re helped by the wonderful Swiss watchmakers of yore though and this is certainly one of those times. This movement, by all rights, should not work properly. It was received in a ziplock bag with a handful of other chronograph movements covered in old oil and grime. It’s nearly eighty years old. Yet after a good clean and installation of a new Mainspring it jumps back to life and with no adjustment to the hairspring or balance, keeping solid time in multiple positions.

A clue to why this is resides on the dial. It reads Universal Genève Uni-Compax H.P.C. H.P.C. is an acronym for High Precision Chronometer and this implies Universal adjusted this movement in multiple positions for the purpose of certification as a Chronometer. It’s an unusual thing to do although Chronometer certification still exists today and high end watches will sometimes carry markings confirming their certification by the COSC.

Now satisfied that this movement has a bit of life ahead of it, I set to work on the chronograph mechanism taking a bit of extra care when removing rust, polishing screws, and regraining the steel levers and springs.

I adjusted the depth of the gears for the chronograph to ensure proper function then set it to work; it has been ticking happily now for several days.

Having completed my first Universal chronograph service I can now compare the movement to some of the chronographs I’ve worked on before. I’m impressed with Martel’s work. The engineering of this movement and the finishing are certainly on par with Venus, Valjoux, and Lemania. I particularly like the fact that there is only one wire spring in this whole movement (all the rest are milled steel). A lot of time went into its production and it’s a shame the case and hands have gone missing. Lastly, I am particularly enamored with the gold plating. Gold plated watch movements are quite uncommon and that alone makes this one feel special. A look back at Universal’s back catalogue suggests this was the norm for their chronographs.

So now what should I do next? An Excelsior Park EP-40?

One thought on “Universal Genève Uni-Compax”